Not that what I have been writing hasn’t been real, but it has been, necessarily, superficial. Travelogue is all well and good, but it is, as Thoreau once wrote about any biographical facts, like a journal of the winds that blew while we were here. Our real lives are internal, reflected in the external, not the other way around.

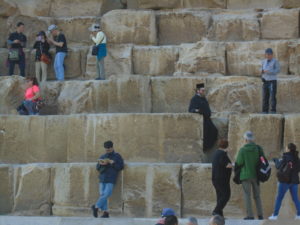

As my body was transporting me from place to place, from event to event, I was not necessarily as interested in where I was as in how I was. I went to Egypt not in search of photographic subjects nor interesting information, but in search of me.

Now, you might well ask, how could any particular geography affect one’s internal affairs? Landscape, scenery, even the people you meet and interact with – how can any of that touch you at your core? Yes, you might have interesting experiences, but you might have had interesting experiences at home. Why should the foreignness of a foreign land have value for you, beyond satisfying your curiosity?

It isn’t that easy to explain. Here’s my best attempt so far.

Our society thinks that time works like this: a present moment that is real, surrounded by past moments which were real but have ceased to exist, and future moments that will be real, but don’t exist yet. In effect, the modern mind thinks, we leap from a present moment that is crumbling beneath our feet to another present moment that isn’t yet there.

That would be some acrobatics! But there’s another way to look at it that makes more sense to me.

Look at it this way: What if every moment of time exists and continues to exist whether we have “come to it” yet or not, whether we have “moved on from it” or not? In other words, what if moments of time are more like our everyday experience of geography than like this hairbreadth-harry idea of the present moment being the only thing that’s real? In geography we would never dream of thinking that the place we just left had ceased to exist, and the place we were moving toward hadn’t yet been created, even though, so to speak, the railroad tracks were headed there.

If this idea is new to you, it may seem fanciful. But play with it, and perhaps you will find that it makes sense of many of the conundrums of life. Either way of seeing the world shows us the present moment as our point of application; common sense does the same. That’s our experience of life, after all. But only the view that says that past and future moments exist and continue to exist makes sense of well-reported time-slip phenomena.

But this isn’t the place to try to “prove” what can’t be proved. You are either going to consider it as reasonable or reject it. (Either way, your reaction will probably have more to do with your emotional makeup than with intellectual process.) The point here is that if all moments of space-time exist and do not cease to exist, then, since we cannot revisit past times at will, perhaps we can connect by revisiting the places associated with those times. And that’s what I went to Egypt to try to do.

Of course, any such attempt comes with potential pitfalls rooted in our psychology. It is so easy to fool ourselves! It is so easy to (on the one hand) persuade ourselves that something is so because we want it to be so; thus we come home convinced we were King Tut, or Nefertiti. It is equally easy (on the proverbial other hand) to persuade ourselves that nothing is happening, because it is important to some part of our psychology that nothing could be happening. Thus we come home triumphantly convinced that nothing happened because we are way too rational to believe in such nonsense.

You can fool yourself in either direction, with too much credulity or with too much skepticism. The trick is to be open to experience without structuring it, thus avoiding both pitfalls. How I set out to do that, and with what results, will constitute another post.