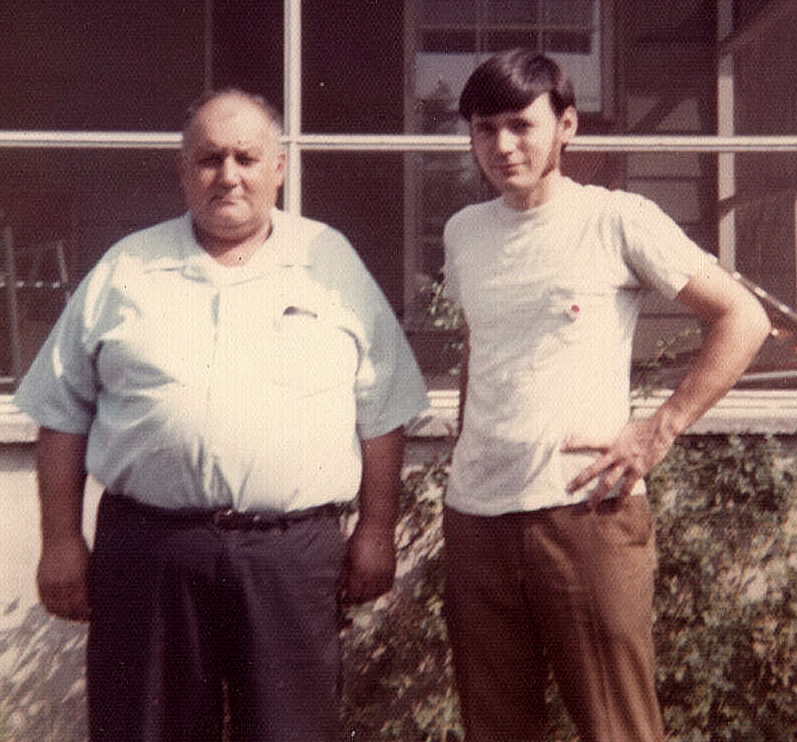

The funny-looking guy on the right-hand side of the photo is me sometime in the early 1970s, complete with long sideburns, a thick long mop of hair, and a frame that now by comparison appears skeletally thin. The man I’m standing next to is my father. March 6, 2012 makes 27 years since he left us, age 70, less than five years older than I am now.

* * *

It is proverbial that children are slow to appreciate the virtues of their parents. Children observe everything, and are often unaware of the true interpretation of what they observe. So, they make judgments, sometimes harsh ones, and years may go by before they see things in a different light. Perhaps it is most often true of sons and their fathers.

Yeats in one of his autobiographies, I think it was, wrote, rhetorically but accurately, “Why does the struggle to come to truth take away our pity, and the struggle to overcome our passions restore it again?” That may not be an exact quote — probably isn’t, as it is from memory — but that’s the gist of it. Very appropriate for fathers and sons. The young man, seeking his place in the world, desperate for certainties, looks on the life of his father with some condescension, perhaps with some scorn. The older young man, having seen that life is not so easy in execution as it appeared in conception, looks back and thinks that perhaps his father didn’t do so badly after all.

My father was fat. That was probably the first thing people noticed. At his most corpulent, he weighed 280 or more. Obesity is one of those characteristics that people are very free to condemn as obviously the result of some moral failing, intemperance if nothing else.

And, dad could be very grouchy, very unapproachable. Although he was not one to stay mad, it didn’t take him long to get there! Nor was he a man of wide sympathies; he was quick to condemn an idea as “simple” (as in simple-minded), one of his favorite pejoratives. And there you have about exhausted the list of his failings. The longer I have lived, the more impressive I find his long list of virtues and achievements.

He was smart, and he was versatile. He could do just about anything he set his mind to, from building a tractor out of two old cars as a young man, to mastering every aspect of farming a small farm in a time when large ones were pulling in six-figure subsidy checks, to building houses as his own contractor and participating in doing every job but putting in the bathroom tiles. He was quick with figures, out-figuring people using calculators. He did his own taxes, and his sisters’, and several of his friends’. He had daring, at one point having borrowed a total of a quarter of a million dollars — fifty years ago! — to finance buying and rehabilitating houses. And he was a shrewd judge. God, was he shrewd! I, being idealistic and systematically mis-educated by a clerical education, believed more or less what I was told. Dad knew better, and no doubt despaired of me many times.

And, mostly, he was kind, and generous, and had a lot of friends and deserved to have them, and kept them. Although he was quick to condemn a theory or a way of seeing things, when it came to people he was accepting, friendly, and non-judgmental. In short, an admirable man.

Well, enough of this. You’re not going to get a sense of him from somebody writing about him, and that isn’t what I wanted to do here. My point is something that perhaps you wouldn’t expect in this connection.

For much of the time Dad was alive, I was too young to appreciate him. It was only in his final decade that he and I came closer to understanding and appreciating each other. (I was in my 40th year when he died; time enough to have learned a thing or two.) But after someone dies, you know how we often think, “I wish I had told him,” or “I wish I could ask his advice now.” It is my great good fortune that in time I learned how to do exactly that, and have done so more than once. And the nice thing is that since our communication is now mind-to-mind rather than personality to personality, we can really understand. As in all communication with those in the non-physical, what you know, they know. There’s no concealment, but no misunderstanding either. It’s nice.

The bad news is that sometimes it takes too long to appreciate our parents. The good news is that it need not be too late to talk to them just because they’ve left the body. In fact, it may be that you come to truly understand each other only then, for the first time.

Like Dad and me.

A nice tribute, Frank.

It also shows that perceived ideas that have been held can be modified over time. The idea of communicating after the fact holds the promise of resolution of estrangement and finding the truth of painful past situations. Thanks

Yes, it opens up a sort of freedom to us. That dead end wasn’t a dead end forever, perhaps ; that unhappy ending wasn’t all that final. And since we can heal our own end of the problems, presumably we can sometimes help those now in the nonphysical to heal their end, as well.

Thanks, loved the picture and the remembrances of yours.

Certainly nice memories. At least those of us who have had the opportunity in the experience of the particular time-sequence.

One thing is for certain….the newer generations have not experienced all of the fun brought to us throughout the decades from the 1950thies unto the 1970thies…in a way it is felt as “the innocent days” one way or the other, despite of the wars going on around.

Well, you know, I think that every generation’s experience is made brighter by the light that is around us in childhood (as Wordsworth once said, in somewhat different words). It isn’t that the times were better so much as that our perceptions were wide open then.

A lovely vinyette and remembrance and a great gift to the both of you that you did learn to see his good points. I am guilty of the same patterns. Perhaps it is our time- an age of idealism. I am at a similar stage in life and been writing about and to my father of late. And now that I am living with my mother full time I have enormous compassion for the man! (smile). Thanks for pointing me here.

Thank you for sharing. I never knew my father, and thus did not have the opportunity to explore that type of relationship.

I do not know if the model/ construct that you have created allows you to explore the relationship between you and the energy that was your father in this life, as you lived in other lives.

My model/ construct contains, as you know, some form of predestination. It is my feeling that when we enter the physical, it is with the understanding that relationships will be formed with certain attitudes, conflicts and bonds. Thus we can explore these aspects of emotion while generating Loosh, which RAM reported to be of value Sonewhere.

Of course, my model will not correlate with yours, but sometimes we have some degree of resonance in the perspectives.

🙂

> I do not know if the model/ construct that you have created allows you to explore the relationship between you and the energy that was your father in this life, as you lived in other lives.

I’m not sure I understand you. If you mean, can I talk with Dad now, the answer is yes, but I think you understood that. So, is the question, can I talk with other aspects of him? Other lives he has led?

Thanks for sharing this, Frank. March 6 is also my son’s birthday, and your thoughts certainly get me thinking about my relationship with him. I have a difficult relationship with my father, and tried very hard to make his experiences better. If not, there’s always grandchildren, right?

Do you communicate with Dad in the same way that you communicate with TGU? Why doesn’t Dad appear in any of your books? Or am I confused and is “Dad” a part of “TGU”? Sorry if I sound dense!

you don’t sound dense. Communication with Dad is as with anyone else. (Dad means my father, nothing else.) He isn’t in a book (yet, at any rate) but then, neither are scads of others i’ve talked to. It depends on the theme, who appears.

My mother and I were estranged through almost all of my adult life, reaching a point of being able to communicate without mayhem only a few years before her death. I was able then, as she was going blind, to support her via email, and have had family feedback that it was of high value to her. I had no regrets of having left things unfinished when she died in 2005, although I do wish we could have known each other as equals over a longer period of time. I assume she knows now of my love, and that is enough.

Nice. Plus, of course you can talk to her still. Even if you can’t hear the response — and better if you can! — it is nice.

Nice portrait, Frank. I remember him well. I sat with him once in that little study he had in the Vineland house — the one sort of off the staircase — talking about all of the books he had crammed on to the shelves.

That must have been the weekend we went to the beach, in the spring of 1969 — and came back to the university to find David in the hospital.

That was, indeed, the weekend.