My ever-helpful brother Paul sent me an article that appeared in The New York Times nearly two years ago. I disagree with her assessment of Lanny’s character as a man of action rather than of introspection, but difference of opinion is what makes horse races. Not only an interesting article on its own, but particularly in context of the two Upton Sinclair communications posted here.

Revisit to Old Hero Finds He’s Still Lively

By JULIE SALAMON

Published: July 22, 2005

When I was about to turn 12, my mother came across a set of familiar books in a sale bin at a secondhand bookstore in Cincinnati, about 60 miles from our home in rural Ohio. She remembered being mesmerized when she read them years before, and bought the entire set for me, for my birthday.

Upton Sinclair, shown in 1933, wrote 11 Lanny Budd books, including a Pulitzer Prize winner.

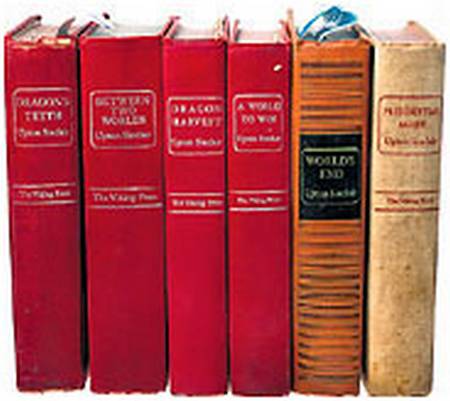

Six volumes of the Lanny Budd (or World’s End) series.

The pages were yellowed, and the red cloth jackets were worn. But I knew the minute I began reading the Lanny Budd series that this was a significant gift, a sign that my mother considered me very grown-up. There were 11 volumes in all, covering the first half of the 20th century in 7,424 pages. The heft wasn’t merely physical. These historical novels engulfed me in the thrilling and terrible imperatives of history that had deeply affected my parents directly but seemed far removed from my time and place, a placid corner of Appalachia.

I assumed that out in the big world, everyone must know about Lanny Budd. But later, after I left Ohio and lived in Boston and then Manhattan, I found that no one I met, whether part of the literati or not, had ever heard of the books. The name of their author, Upton Sinclair, always evoked the same response: “Oh, yeah, I read ‘The Jungle’ in high school. ”

Why had the Lanny Budd books been forgotten in relatively short order? They were international best sellers when they were published by the Viking Press – primarily in the 1940’s, not the 19th century. “Dragon’s Teeth,” third in the series, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1943. Their dust jackets carry blurbs to die for, from luminaries including H. G. Wells, Albert Einstein, Thomas Mann and George Bernard Shaw, whose quotation reads: “When people ask me what has happened in my long lifetime, I do not refer them to the newspaper files and to the authorities, but to Upton Sinclair’s novels.”

But these novels, which had been published in 21 countries, quickly became obscure. My mother first read the series in the early 1950’s, about the time it was completed. She found Lanny Budd by accident. She was a recent immigrant, and went to the library hoping to find another book by Sinclair Lewis, whose writing she had enjoyed in Hungarian translation back in Europe. Perhaps flummoxed by her accent, the librarian sent her home with “Dragon’s Teeth” by Upton Sinclair.

That case of mistaken literary identity evolved into a literary infatuation. Sinclair’s Lanny Budd – worldly, dashing, but possessed of a social conscience – meshed perfectly with my mother’s own romantic, political and historic yearnings. She has always been a persistent optimist, despite her own grim World War II experiences as a European Jew and concentration-camp survivor. Lanny was a bon vivant who had the means to avoid engagement with the world’s misery, but instead became a behind-the-scenes player, often at great risk but always escaping to face the next chapter’s conundrum.

Along with the books, my mother transmitted her passion to me. I read all 3 million words before my 13th birthday. And then I never opened the novels again, though they’ve remained prominently displayed on my bookshelves. I could say my neglect came from having so much else to read. But I often revisit books I’ve loved.

No, I kept away from Lanny because I wanted to keep my fond memories intact. I’d become aware that Sinclair is not held in literary esteem, being remembered most for his socialist polemics, his failed attempt to become governor of California and his fascination with the paranormal. Would Lanny simply seem ridiculous to me now, like so many heartthrobs from my adolescence?

The World’s His Stage

So it was with trepidation that I returned to Lanny Budd last January. I’m not sure why I did. Perhaps I was inspired by the arrival of the 60th anniversary of World War II’s end, or by observing my own teenage daughter’s growing fascination with global history, sparked by a charismatic teacher. Whatever the reason, one cold and gloomy day I opened “World’s End,” the first book in the series, published in 1940. An odyssey of several months began with these words:

“The American boy’s name was Lanning Budd; people called him Lanny, an agreeable name, easy to say. He had been born in Switzerland, and spent most of his life on the French Riviera; he had never crossed the ocean, but considered himself an American because his mother and father were that. He had traveled a lot, and just now was in a little village in the suburbs of Dresden, his mother having left him while she went off on a yachting trip to the fiords of Norway. Lanny didn’t mind, for he was used to being left in places, and knew how to get along with people from other parts of the world. He would eat their foods, pick up a smattering of their languages, and hear stories about strange ways of life.”

Lanny was 13 in that introduction and impossibly glamorous. Born in 1900, he was the illegitimate child of an American arms merchant and his mistress, named Beauty, who raised their son on the Riviera while her ex-lover maintained a respectable life with a wife and children in Connecticut. In that childhood on the Côte d’Azure, Lanny mingled easily both with local peasants and wealthy dilettantes. Over the course of the series, Lanny became a participant in almost every moment significant to Western history in the first half of the 20th century. But unlike subsequent fictional witnesses to world events, he was neither a nebbishy chameleon like Woody Allen’s Zelig, nor a noble Everyman like Forrest Gump. Things didn’t happen to Lanny; he helped make them happen.

Using his father’s conservative credentials and his own facade as an international art dealer, Lanny became a confidant of Hitler and Goering. He operated as a secret agent for President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He charmed Einstein by playing excellent piano accompaniment to the scientist’s violin and risked his own life to rescue a Jewish friend from concentration camp. He spoke many languages fluently, casually quoted from Goethe and Byron, dabbled in both physics and metaphysics, and was a socialist and feminist while always behaving like a Victorian gentleman.

A Man of Action

When I completed the 10th volume last week, Lanny was 45, and World War II was over in Europe. (I still have one final volume to go, “The Return of Lanny Budd,” which takes place during the cold war.) I felt exhilarated and relieved to discover that I hadn’t been a fool – far from it – for being mesmerized by the series. Yet I also understood why Lanny Budd had fallen out of fashion.

Sinclair, who had been a muckraking journalist, wrote the books with deadline urgency. And he was facing a deadline, a big one. World War II was well under way in Europe when he began. In a statement Sinclair prepared for the Literary Guild, which had made “World’s End” one of its selections in 1940, he wrote: “Fate has put you and me upon the earth in one of the critical periods of human history; a dangerous time, but exciting – certainly there has never been a time when it has been possible for the ordinary person to know so much about what is going on.” He then continued: “I saw the rise of Mussolini, and of Hitler, and of Franco; the dreadful agony of Spain wrung my heart; then I saw Munich, and said to myself, ‘This is the end; the end of our world.’ ”

Even for a facile writer (he wrote more than 90 books in his 90 years, as well as numerous plays and articles), he was writing fast, producing the first 10 volumes in 9 years. So there is repetition; he often reminds the reader that Beauty, Lanny’s mother, must diet to ward off “embonpoint” (French for plumpness). Character development is not of primary concern: Lanny is a man of action, not introspection. The insouciance with which he handles adversity, so admirable when I was a child, can now seem an annoying absence of psychological depth. But Sinclair’s historical acumen and his calculations about powerful institutions – government, press, corporations, oil cartels and lobbyists – remain remarkably shrewd and often prescient. Surely there is enough there to compel at least some of the minions devoted to the History Channel.

I wanted to talk to somebody about the books. My own family had patiently endured my tendency to evoke the series in conversations covering a wide variety of subjects, especially Iraq and Karl Rove. But when one of my children stopped me one day and said, “Oh no, not Lanny Budd again!” I decided I needed to find other devotees of the series.

‘An Entrancing Protagonist’

They do exist. On the Internet I found Andrew Simon, a retired engineering professor living in Florida who six years ago began a publishing company called Simon Publications (simonpublications.com), which specializes in books Mr. Simon considers long-lost classics, mainly history books. Four years ago, Mr. Simon republished the Lanny Budd series, which in his paperback version comes in 22 volumes because the print-on-demand technology he uses can’t handle books longer than 750 pages.

I spoke to him on the telephone and discovered we had other connections. Like my mother, he spoke Hungarian, and he had lived in Ohio for 30 years, teaching civil engineering at the University of Akron. He had read the Lanny Budd series in Hungary, in the late 1940’s, but said he had to wait until immigrating to the United States to read the final volume because of its anti-Communist views.

What drew him to the books? “I felt they were very, very correct in a historical sense,” he said. “Though he was an American, he described Europe and European ways and thinking just as it was at the time.” Sales have been so-so, he said, about 100 to 150 copies of the series every year.

Lauren Coodley, a professor of history and psychology at Napa Valley College, edited an anthology of Upton Sinclair’s writings, published last year, called “The Land of Orange Groves and Jails: Upton Sinclair’s California” (Heyday).

She told me she had been trying to revive interest in Sinclair for a decade, since a friend handed her one of the Lanny Budd novels. “He is such an entrancing protagonist,” she said in a telephone interview. “The American abroad, the educated American of conscience. He stands for the dilemma of Americans in the world, of deciding what’s a good life, how much to enjoy yourself and how much good to do.”

Trying for Art

Maybe Lanny Budd will rise again. He is the subject of a chapter in “Upton Sinclair: Radical Innocent,” a biography by Anthony Arthur scheduled for publication by Random House next year.

Professor Arthur, a retired professor of literature at California State University in Northridge, told me he, too, had been wondering why the Lanny Budd books had more or less disappeared. “He was always regarded as a kind of guilty pleasure,” he said of Sinclair. “There are writers today that have that reputation, like Tom Clancy or Robert Ludlum, but his style is infinitely superior to popular writers today who are praised for their adventure stories.”

Then he asked, “Did you notice how much untranslated German there is? Sinclair was condescended to by intellectuals who said he was writing for the middle class with a mild interest in ideas and negligible grasp of issues. If that’s true, then the level then was a good deal higher than it is today.”

For Professor Arthur, the Lanny Budd series marked a significant passage for Sinclair, who was in his 60’s when he started writing the books. “He’d been tagged all his life with being a propagandist,” Professor Arthur said. “This was his moment of decision to become the closest thing to a pure artist that he could.”

I have returned my Lanny Budd books to their shelf. Maybe one day my children will feel the urge to have a look and keep our family’s literary infatuation going for one more generation.

Upton Sinclair in 1942.

Lanny Budd Series

‘WORLD’S END,’ 1940; 740 pages. World War I and immediately after.

BETWEEN TWO WORLDS,’ 1941; 859 pages. From the Treaty of Versailles (1919) to the crash of 1929.

‘DRAGON’S TEETH,’ 1942; 631 pages. (Pulitzer Prize winner); 1929 to 1934 – the Nazis’ rise to power.

‘WIDE IS THE GATE,’ 1943; 751 pages. 1934 to 1938 – the Nazi blood purge and the Spanish Civil War.

‘PRESIDENTIAL AGENT,’ 1944; 655 pages. 1938 – the appeasement period.

‘DRAGON HARVEST,’ 1945; 703 pages. From Munich to the German occupation of Paris.

‘A WORLD TO WIN,’ 1946; 627 pages. Vichy – 1940 to 1942.

‘PRESIDENTIAL MISSION,’ 1947; 645 pages. 1942 to 1943 – the African invasion and behind the scenes in wartime Germany.

‘ONE CLEAR CALL,’ 1948; 629 pages. 1943 and 1944 – Sicily, Italy, France: D-Day to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s re-election.

‘O SHEPHERD, SPEAK!,’ 1949; 629 pages. 1944 to 1946 – Battle of the Bulge, Yalta, Roosevelt’s death, the first A-bomb, the Nuremberg Trials.

‘THE RETURN OF LANNY BUDD,’ 1953; 555 pages. The cold war.

Related Books

‘THE LAND OF ORANGE GROVES AND JAILS: UPTON SINCLAIR’S CALIFORNIA,’ edited by Lauren Coodley. Heyday Books; 215 pages; $18.95

UPTON SINCLAIR: RADICAL INNOCENT,’ by Anthony Arthur. To be published by Random House in 2006.