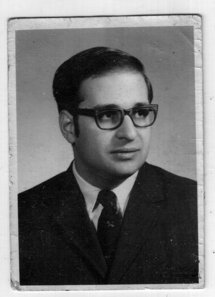

Dave

It was Sunday nigh, late.t May, 1969, the final month of my college career at George Washington. I was standing in the empty living room of the fraternity house when Dennis came in. “Yo, Crabb,” I said. “What happened to you guys?” He and Dave Schlachter had been expected to join us – Dale, my roommate Bill, me, my fiancé, and my brother Paul and sister Margaret – for a weekend at my uncle’s place on the Jersey shore. But they hadn’t come.

I expected a casual apology, or sincere regrets, or a good-natured insult, any or all. Instead, he came to a dead halt and chilled me with a sober question. “Nobody told you?”

“We just got in three minutes ago,” I said. “I haven’t seen anybody. We dropped Dale off at the apartment. We were going to tell Dave and you what you’d missed, but you weren’t there.” I could hear the words rattling out, and I made myself stop. “Dennis, what’s wrong?”

He was looking at me steadily, almost without blinking. “Dave is in the hospital. I just came over here to get his car. I have to pick up his parents at National, their flight comes in at 11:25.”

Flying in from Iowa? “What the hell happened?”

“He started seeing double.”

I said, “I suppose that explains the headaches, but what’s he doing in the hospital? Why not the eye doctor?”

“Frank, when people start seeing double, doctors think brain tumors.” He started down the hall toward the back door. “I took us to the hospital in Dave’s car, but I had to leave it here or I would have had to move it every couple of hours.”

Apparently Dave had gone to bed without supper on Friday night, plagued by another of the monster headaches that had haunted him all semester. Saturday morning, he had awakened seeing double, and had had Dennis dial the phone so he could talk to his parents, who of course had told him to get seen right away. Dennis had helped him get trousers and a sweater over his pajamas, and had put socks and loafers on his feet, and had driven him to the emergency room at GW Hospital, a mile or two from their apartment, though only a few blocks from campus. After an endless wait in the emergency room, the doctors had admitted Dave “for observation.”

I said, “So why are his parents coming? Why aren’t they waiting for something definite?”

His mouth was a harsh expressionless line. “Because I called them and told them that now Dave can’t even move.”

“Jesus.” That was all I seemed able to say. Dennis got into Dave’s car. “You want company?”

He hesitated. “Yeah, I guess I do, but it would be nice to have somebody at the hospital until I get his parents there.”

“You mean Dave’s alone? Where are all our beloved brothers? Do they even know?”

He turned the key in the ignition. “Of c—. I don’t know. It seems like I told somebody, but I couldn’t absolutely swear to it.”

“Okay, I’ll get the word out, and I’ll get over to the hospital. Got to tell Bill and Dale, for sure.”

“I left Andrews a voice-mail message. He’s probably on his way.” He started to back the car.

“Hey Dennis, what room? And will they even let me in, do you think?”

“They might, if you think up a good enough story. Room 406.”

“406, okay. Dennis –” It embarrassed me, but I said it anyway. “Be careful, okay? We don’t need any more complications.”

“Yeah,” he said, and he was gone.

Visiting hours were long over, of course, so when Bill and I walked into the lobby, we went right for the stairs instead of standing waiting for the elevator. If anybody noticed us, they didn’t say anything. We stepped out onto the fourth floor hallway, entirely too close to the nurses’ station. There were two nurses sitting there, one writing, one filing. We walked off in the other direction. I concentrated on trying to make my footsteps sound authoritative and confident.

Fortunately, 406 was just two doors down, its door half open. It could just as easily have been on the far side of the nurses’ station. Carefully, quietly, we entered the darkened room. A figure standing beside the near bed looked up.. a doctor. Sharply: “Yes?”

“Th- that’s my brother,” I said. Well, he was, wasn’t he?

“Wait outside, please,” the doctor said firmly. When he came out, he was looking tired. “Now then, how did you boys get in here?”

“Doctor, that’s my brother in there,” I said again. “His – our parents live in Iowa. They’re are on the way in, but I don’t want him to have to wait for them alone. We won’t make any noise, and we won’t disturb him.”

He looked at me from the height of 40 or 50 years. “His brother?”

“Yessir. I’m visiting him this week.”

One side of his mouth turned up, just a bit, skeptically. “And I suppose this is another brother?”

“Cousin, sir,” Bill said promptly, all sincerity and humility.

“No doubt. Well, boys, listen to me. Your – ah – relative is very sick. He is much too sick to have visitors at the moment. He needs all his strength. Your seeing him can’t do him any good and might easily do harm. Do your understand? Your wanting to be here with him does you credit, very commendable – but you cannot see him. I suggest you go home.”

He had been walking toward the nurses station, us following. I said, “Thank you, doctor,” for the nurses benefit. “We understand.”

“Yes, well, nurse, just so there is no question about it, the patient in 406 is not to receive visitors. Good night, boys.” He stabbed the elevator’s “down” button and did not insist that we accompany him. Later, thinking about it, I took that to be an extraordinarily kind gesture, but maybe he wasn’t going to the ground floor, or maybe he figured it wasn’t his business to act as policeman, so long as we stayed out of Dave’s room.